Recent research from the Bias Homicide Database finds that people are killed every year by hate or bias crimes because of who they are perceived to be or what they represent. Victims may be targeted solely because of their race, ethnicity, where they worship, who they love, how they express their gender, where they come from, or if they have a place to call home. In other cases, discriminatory selection of victims based on their status or identity occurs in combination with other more common criminal motives, including revenge and robbery.

Still a relatively rare form of violence, we primarily learn about hate and bias crimes through news stories that familiar scripts or narratives.

One bias crime storyline follows high-profile mass shootings, like the Pittsburgh Synagogue shooting, the Pulse Nightclub Shooting, and the Charleston Emanuel AME Church shooting. Reporters and their sources raise questions about motive – was the offender fueled by hate, white supremacy, a terrorist ideology, or some other nefarious motive?

Other stories are based on the release of annual crime statistics that suggesting increases or decreases in the number of hate crimes committed in the United States. Crime experts are called upon as mews sources to remind us of the consistent underreporting of hate crimes by police, while policy makers debate changes to laws and reporting practices.

Missing from this conversation are reliable data on the types of people who continue to commit these crimes, who is most likely to be killed, and the circumstances in which people are murdered for simply being themselves.

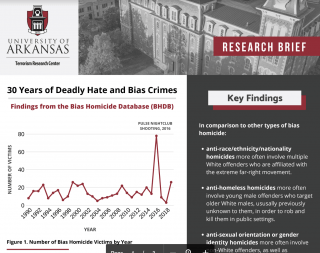

Fortunately, new findings from the Bias Homicide Database (BHDB) are beginning to illuminate the nature of bias homicide in the United States. Housed in the Terrorism Research Center at the University of Arkansas, the BHDB includes information on approximately 350 felonious murders. For every bias homicide, data on attributes of victims, offenders, and the circumstances in which victims were killed are tracked, with data spanning back to 1990.

For a case to be included in the database, there must be evidence in open-source materials that victims were selected in part or wholly based on some element of their identity or social status. The creation of the BHDB aligns with an increasing number of researchers who are creating databases based on information from publicly available sources to study relatively rare forms of crime, such as mass shootings and terrorism. Over the last several years, researchers have increasingly begun to use publicly available information to create their own crime databases in order to fill in the gaps left by inconsistencies in official crime reporting.

Hate crimes continue to remain undercounted, despite most U.S. states now having some form of hate crime law on the books. For a variety of reasons, there is simply no way to discern in official crime data when homicides are committed as acts of terrorism, hate crime, or some other form of targeted violence.

Currently, the BHDB is the only open-source database that includes comprehensive information on bias homicides regardless of offenders’ affiliations with domestic extremism. A recent research brief published by the Terrorism Research Center found that evidence of affiliations to far-right extremism for bias homicide offenders ranged from approximately 10% to 44%, depending on the type of victims targeted. Offenders who targeted victims because of their sexual orientation or gender identity were the least likely to be associated with the domestic extreme far-right, while the opposite is true of offenders who targeted victims based on their perceived race, ethnicity, or nationality.

Currently, the BHDB is the only open-source database that includes comprehensive information on bias homicides regardless of offenders’ affiliations with domestic extremism. A recent research brief published by the Terrorism Research Center found that evidence of affiliations to far-right extremism for bias homicide offenders ranged from approximately 10% to 44%, depending on the type of victims targeted. Offenders who targeted victims because of their sexual orientation or gender identity were the least likely to be associated with the domestic extreme far-right, while the opposite is true of offenders who targeted victims based on their perceived race, ethnicity, or nationality.

Other key findings from the research brief reveal differences in the nature of bias homicide depending on who is killed. For instance, while anti-religious homicides have occurred less frequently over the last 30 years, they are often the deadliest with multiple victims being killed in a single attack. While persons who are homeless are only considered a protected group in some states, data from the BHDB show that nearly 10 percent of all bias homicides across the U.S. discriminately target individuals wholly or in part based on their homed status.

Over 30 years of BHDB data suggest that people being killed simply for who they are or are perceived to be is inevitable. These senseless attacks take the lives of innocent victims every year. Also inevitable are the tired debates about how to label such murders and whether laws are required for justice to be served. Perhaps findings from the BHDB can not only serve to inform this discussion but will also help us to better understand the often-complicated circumstances in which bias homicide occurs and, importantly, the enduring harms inflicted on the families and communities experiencing this form of violence.